If you’ve been to the gas pumps lately then you’re familiar with the fact that our global economy is on the proverbial struggle bus. Gas is one thing, but did you know that in the last year food prices have undergone the largest increases we’ve seen since the late 1970’s? When pondering the economic problems at hand, most pundits only offer solutions that involve doubling down on the obviously broken global economy. However, a seldom discussed aspect of the conversation is how a localized alternative to the global economy is just plain better, economically, environmentally, and ethically speaking.

Here’s the gist:

- Economic: The global food economy is more volatile (and expensive) than local food economies in hard times.

- Environmental: The environmental impact of the global food economy is undeniably negative, while local sourcing of ethically grown food actually benefits the planet.

- Ethical: When wealthy nations compete for the global food supply during hard economic times, the ability of food insecure nations to access affordable food is severely disrupted. In contrast, when wealthier nations source food locally, nonprofits and NGOs are able to access more affordable global food for distribution to impoverished countries.

The Economic Argument

The bottom line is that food produced and sold within a small economy is more affordable than food brought in from elsewhere, especially during hard times.

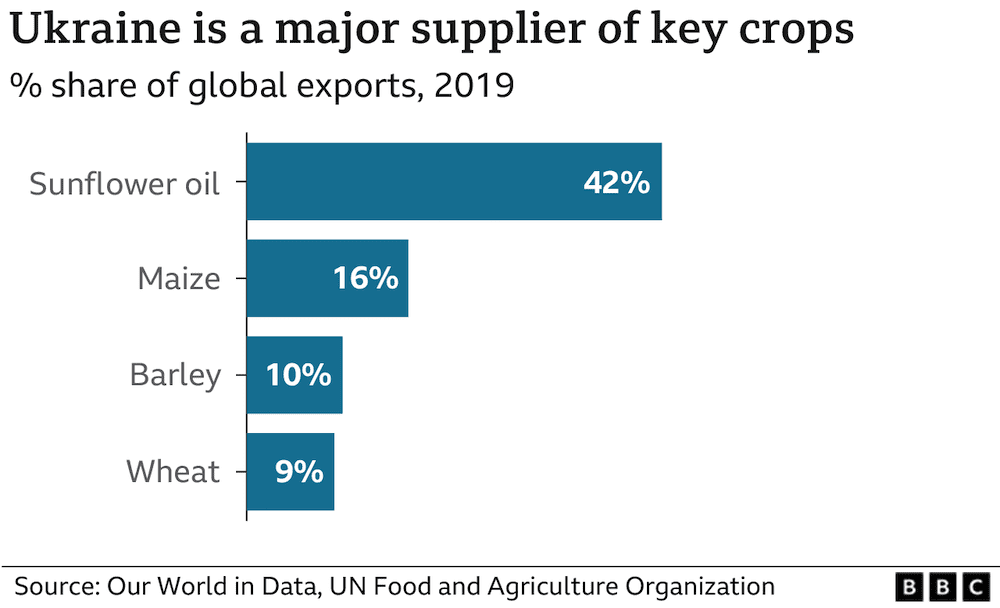

According to the graph below from a recent BBC article, Ukraine is a major global exporter of crops like corn, sunflower oil, and wheat. Because of the continuing war, “Ukrainian farmers have 20 million tonnes of grain they cannot get to international markets.” Simply put, when global supply of a staple product decreases, prices for that product (and anything its used in) increase around the world.

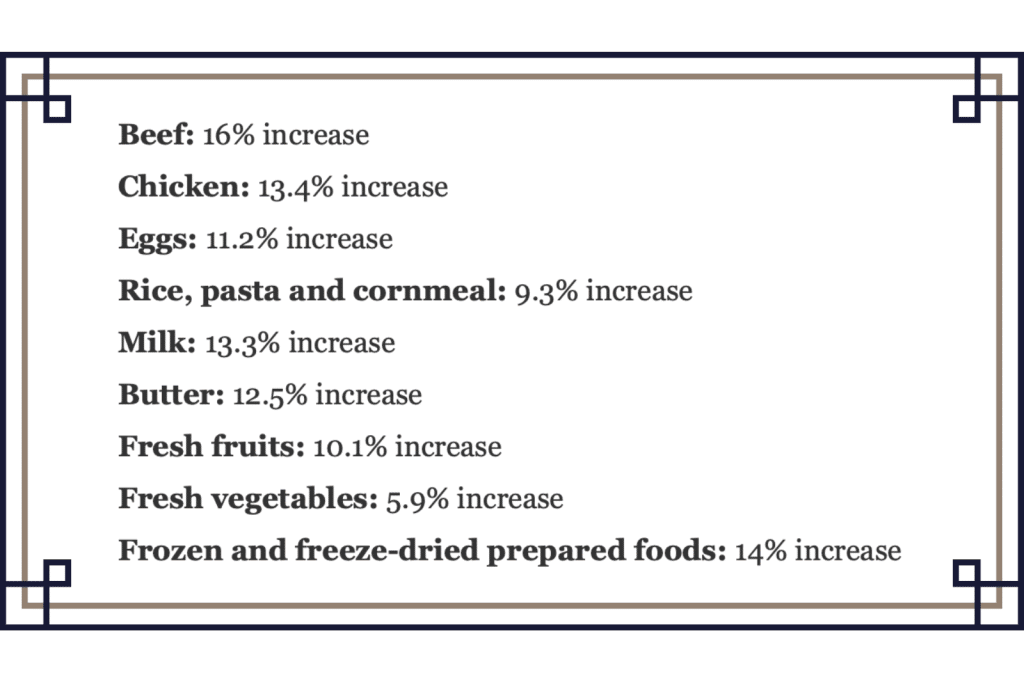

Inflation is affecting food prices at higher rates than many other consumer goods categories, and it’s globalized commodity foods that are increasing most rapidly. A Bureau of Labor Statistics news release published in May shows that, “[t]he food at home index [groceries] rose 11.9 percent over the last 12 months, the largest 12-month increase since the period ending April 1979.”

Unfortunately, because it takes time for rising prices of inputs like fertilizer and fuel to trickle down to the retail level, the worst impacts of war and inflation are yet to come with the next crop of fall produce.

Now compare that with our local food system focused on ethical food production. Our regenerative farmers and food producers don’t depend on a global supply chain to produce or sell their goods, and are therefore sheltered from many of the economic hardships associated with the global food economy. They’re not shipping their produce to California, let alone overseas, and by keeping the supply chain short, they’re protecting local consumers from shortages and exorbitant price hikes, while also cutting down on greenhouse gas emissions.

The Environmental Argument

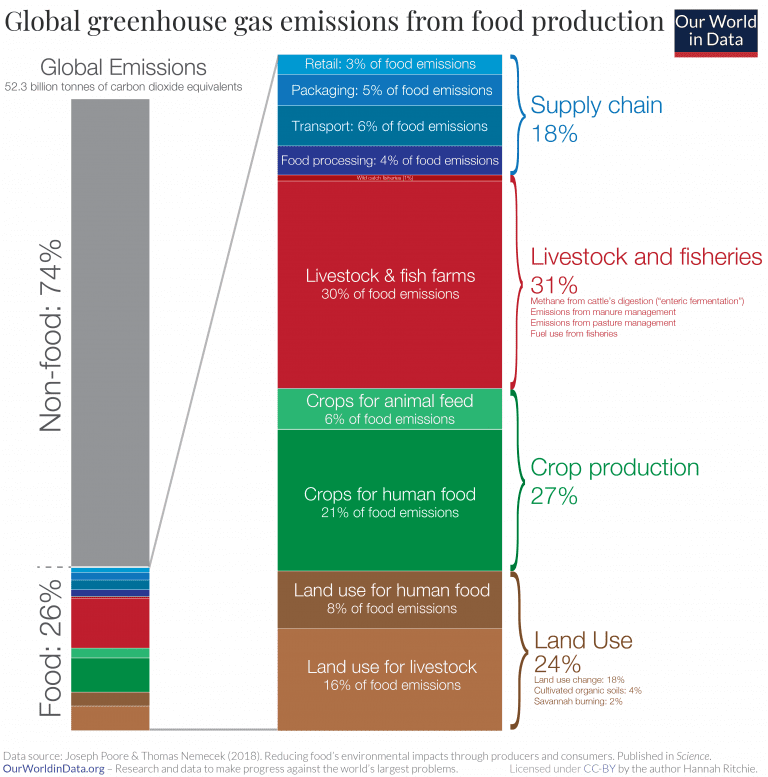

For a breakdown of the commodity food economy’s influence on global emissions, take a look at this 2019 graph from ourworldindata.org. Much of the devastating impact on global emissions is made through industrial agriculture, characterized by growing crops and raising livestock in a way that erodes topsoil, destroys aquatic ecosystems, and has no consideration for the depletion of non-renewable resources.

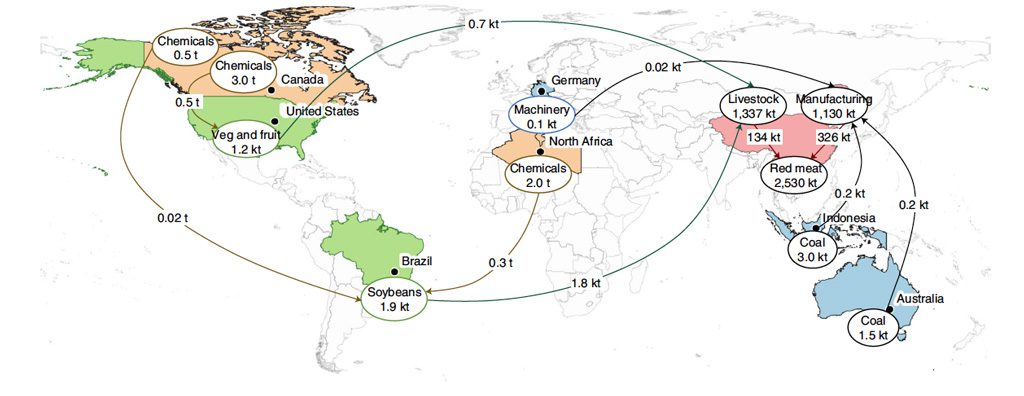

For a more behind the scenes look at how this practically plays out, take a look at what goes into producing red meat for consumers in China. The graph below from carbonbrief.org displays numerous lines that trace a complex narrative of international trade, touching every continent but Antartica to meet China’s demand for red meat.

A healthier alternative to the global industrial ag system is local, regenerative agriculture. Designed to partner with the planet through crop diversification, rotational grazing, carbon sequestration, and resting the land- the regenerative ag method is far superior.

Regenerative farming goes beyond organic, relying on a short supply chain with very few non-local inputs.

This form of farming depends on a small local market of consumers, choosing to eat what’s seasonally available and being rewarded with supremely fresh and flavorful food.

The Ethical Argument

A recent article in Reuters explains that when wealthy nations rely on the global food economy during shortages, the food insecure are more likely to go without eating. And here’s why: remember the 20 million tons of grain rotting in Ukrainian fields and the subsequent global price increase on those products? In our world’s free market economy, limited supply goes to the highest bidder–AKA wealthy nations like The United States–leaving impoverished countries, like Zimbabwe, unable to afford these global goods and ever closer to the brink of starvation.

NGOs and non-profits like the World Food Program can’t compete with the consumer demand of wealthy western nations unless citizens of those nations do two things: donate generously to the WFP and spend their food dollars locally.

The latter will serve to alleviate price increases instead of driving up the cost and competition for global commodity food.

With all this talk, you might be sold on the idea of local sourcing during inflationary periods, but what about when the global economy is doing great? We can’t forget that to have a strong local economy, our support must be year round. Not only when it’s most convenient for us, but also when it’s more of a stretch. Local businesses are small by nature; they aren’t propped up by the government and they aren’t “too big to fail.”